I. Epic Poetry: A Deep Dive into Beowulf

The foundational epic of English literature, blending heroic valor with Christian faith.

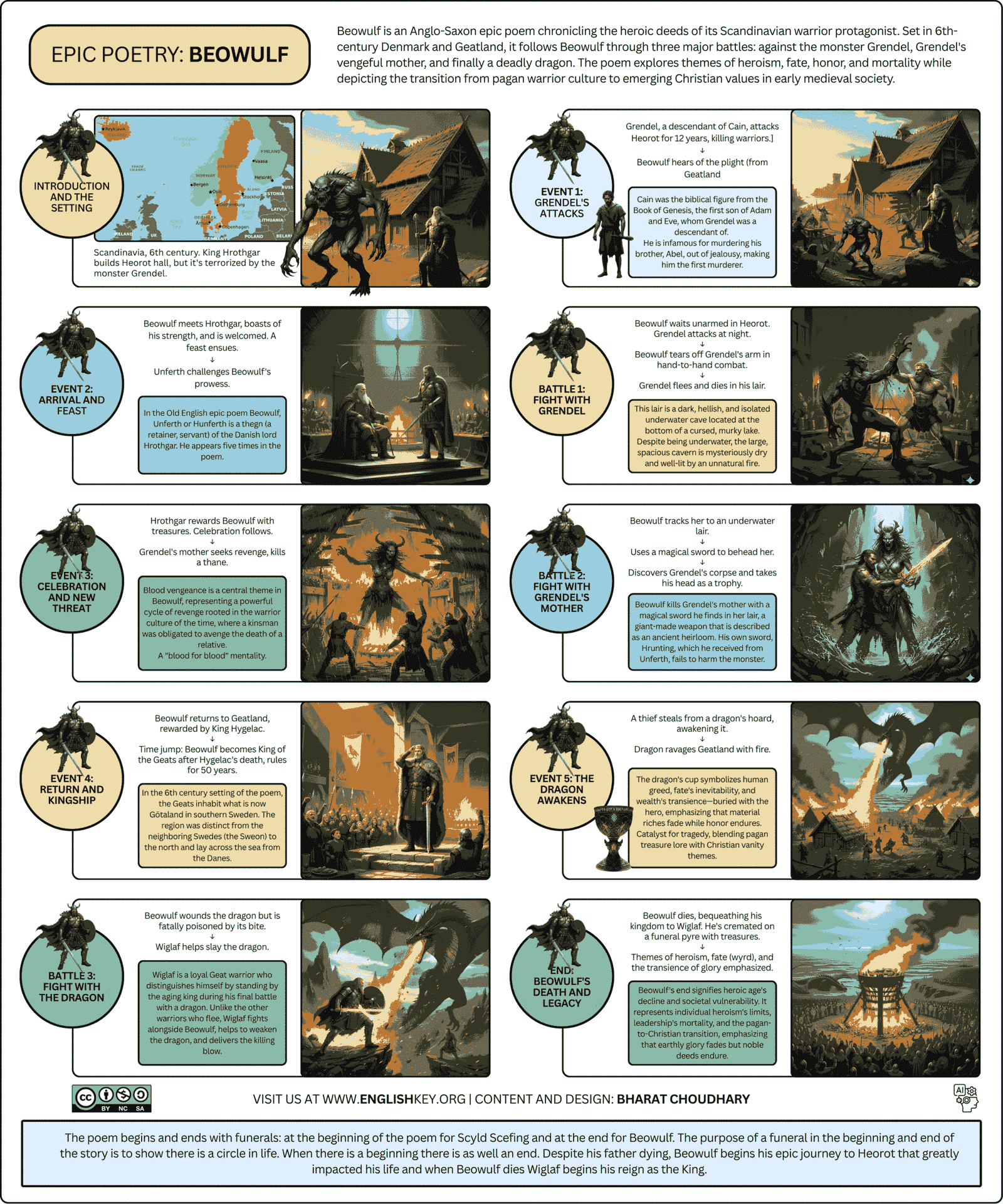

Beowulf is an Old English epic poem, likely composed between the 8th and 11th centuries, though its manuscript dates to around the 10th century. It tells of the hero Beowulf, a Geatish warrior who fights the monster Grendel, Grendel’s mother, and, later, a dragon, embodying themes of heroism, fate, and the clash between pagan and Christian values. It’s one of the most important works of Old English literature and provides rich insight into early Anglo-Saxon culture.

1. Historical and Literary Context

Beowulf is the greatest and earliest surviving epic poem in English literature, composed between the 8ᵗʰ and early 11ᵗʰ centuries. It represents the synthesis of Germanic heroic tradition and Christian moral philosophy, mirroring the social and spiritual transformation of early medieval England.

The poem survives in a single manuscript, the Nowell Codex (c. 1000 AD), written in the West Saxon dialect of Old English. Its authorship remains anonymous, but the poet is believed to have been a learned Christian who reinterpreted older pagan legends through a moral and religious lens.

Though written in England, Beowulf is set in Scandinavia, reflecting the ancestral memory of the Anglo-Saxons’ Germanic roots. Its narrative preserves the warrior code (comitatus), the fatalistic worldview of wyrd (fate), and a deep sense of moral duty — all hallmarks of the Anglo-Saxon ethos.

2. Synopsis / Plot Summary

The poem opens with the funeral of the legendary Danish king Scyld Scefing, symbolizing the cyclic nature of life and kingship. His descendant Hrothgar, king of the Danes, builds a grand hall called Heorot, a center of feasting, unity, and fame. However, the monstrous Grendel, an outcast and descendant of Cain, attacks Heorot nightly, devouring Hrothgar’s men for twelve years.

A Geatish hero, Beowulf, hears of Hrothgar’s suffering and sails with his companions to help. In a fierce hand-to-hand combat, Beowulf kills Grendel by tearing off his arm. The next night, Grendel’s Mother seeks revenge, killing one of Hrothgar’s trusted men. Beowulf dives into her underwater den, slays her with a magical sword, and returns to glory.

He later returns home to Geatland, where he rules wisely for fifty years. In his old age, a dragon, angered when a slave steals a cup from its treasure hoard, ravages the land. Beowulf confronts it in a final act of courage, kills it with the aid of his loyal follower Wiglaf, but dies from his wounds. The poem ends with Beowulf’s funeral and his people mourning the end of an age of heroes.

3. Themes and Moral Vision

- Heroic Code (Comitatus): Loyalty between lord and thane, courage in battle, and the pursuit of everlasting fame (lof) form the moral foundation of the epic.

- Fate and Divine Providence (Wyrd): The poet blends pagan fatalism with Christian faith — man must act bravely, but his fate ultimately lies in God’s hands.

- Good vs Evil: Grendel, his mother, and the dragon symbolize external and internal forms of evil — sin, revenge, and greed — against which heroism defines itself.

- Mortality and Transience: Earthly glory and riches are fleeting; true immortality lies in reputation and righteousness.

- Christian Elements: The poem integrates Biblical allusions — Grendel’s lineage from Cain, frequent invocations of God, and Beowulf’s Christ-like self-sacrifice.

- Kingship and Responsibility: The poem contrasts good rulers (Hrothgar, Beowulf) with prideful ones (Heremod), teaching that wisdom and humility sustain kingdoms longer than brute strength.

4. Symbolism of the Monsters

| Monster | Description | Symbolic Function |

|---|---|---|

| Grendel | Cannibalistic demon who attacks Heorot | Represents jealousy, spiritual damnation, and isolation from divine order |

| Grendel’s Mother | Vengeful creature from the mere | Embodies vengeance, primal chaos, and the destructiveness of maternal grief |

| The Dragon | Treasure-hoarding fire-drake | Symbolizes greed, time, and the inevitability of death |

Each creature mirrors a stage in Beowulf’s life — youthful courage, mature justice, and fatal heroism — forming a moral cycle from triumph to mortality.

5. Form, Structure, and Poetic Devices

Beowulf is written in Old English alliterative verse (3182 lines), the hallmark of Anglo-Saxon poetry. Each line has four stressed syllables, divided by a caesura, with alliteration linking the half-lines.

| Key Stylistic Features | Function / Example |

|---|---|

| Alliteration | Creates rhythm, structure, and emphasis: “Grim and greedy, he grasped the sleepers.” |

| Kennings | Compact metaphorical compounds that enrich imagery: “whale-road” = sea; “bone-house” = body. |

| Litotes | Ironical understatement: “That was not a good exchange” after death or defeat. |

| Caesura | Mid-line pause dividing thought: “Hwæt! We Gar-Dena || in gear-dagum…” |

| Formulaic Repetition | Common in oral tradition to aid memory: “Hwæt!” (“Listen!”) as a call to attention. |

| Digressions and Flashbacks | Provide moral parallels and cultural depth: Stories of Sigemund and Heremod. |

| Epic Diction | Grand, elevated vocabulary emphasizing heroism: Frequent use of noble titles, genealogies, and ritual speech. |

6. Pagan–Christian Fusion

The greatness of Beowulf lies in its spiritual duality:

- Pagan heroism celebrates fame and martial courage.

- Christian morality transforms heroism into self-sacrifice and humility.

The mead-hall Heorot stands for earthly fellowship; the dragon’s cave for material corruption; and Beowulf’s death for moral transcendence. Thus, the poem becomes not merely a heroic saga but a meditation on the moral destiny of man.

7. Literary and Historical Importance

Literary Significance

- The first great national epic of the English-speaking world.

- Prototype of later epics like The Faerie Queene and Paradise Lost.

- Demonstrates early narrative unity, symbolic structure, and thematic coherence.

Historical Importance

- Provides authentic insight into Anglo-Saxon warfare, kinship, values, and social order.

- Reflects the heroic ideal at the threshold of Christian civilization.

Linguistic Importance

- Preserves Old English vocabulary, syntax, and rhythm in its purest literary form.

- A key text for the study of Germanic philology and early English prosody.

Philosophical and Ethical Value

- Explores human courage in the face of inevitable death — a universal theme.

- Expresses the moral evolution of early English consciousness.

8. Quick Revision Chart

| Composition Period | 8ᵗʰ – early 11ᵗʰ century |

| Language & Source | Old English; Nowell Codex |

| Genre & Length | Epic poem, 3,182 lines |

| Setting | Scandinavia (Denmark & Geatland) |

| Main Characters | Beowulf, Hrothgar, Wiglaf, Grendel, Grendel’s Mother, Dragon |

| Structure | Three battles marking youth, maturity, and old age |

| Themes | Heroic code, fate, good vs evil, transience, faith |

| Style | Alliterative verse, kennings, caesura, digressions |

| Tone | Grave, reflective, moralizing, heroic |

| Legacy | Foundation of English epic and moral tradition |

9. Concluding Insight

Beowulf endures not only as a heroic tale but as a moral and spiritual document. It portrays a world where men strive for honour despite knowing death is inevitable, where courage becomes a form of faith, and where the glory of the warrior transforms into the wisdom of the saint.

Its closing lines, lamenting a “mildest and most generous of kings,” echo across centuries as the voice of early English civilization — proud, moral, and deeply aware that true greatness lies not in triumph, but in integrity before fate.

Revision Hub

Consolidate your learning with these study tools.

Narrative Flowchart of Beowulf

Part 1: The Youthful Hero

Hearing of King Hrothgar’s plight, the young Geatish hero Beowulf sails to Denmark with 14 warriors to prove his strength, gain honor (lof), and repay a debt his father owed. He is a hero in his prime, defined by immense physical strength and courage.

Battle 1: Grendel

Representing envy, chaos, and alienation from God (as a descendant of Cain), Grendel attacks the mead-hall. Beowulf, relying on his pure, God-given strength, fights him bare-handed and mortally wounds the monster by tearing off its entire arm.

Battle 2: Grendel’s Mother

Seeking blood-vengeance (a key part of the heroic code), Grendel’s Mother attacks Heorot. Beowulf follows her to a demonic underwater lair and kills her with a giant’s enchanted sword, symbolizing a descent into a pagan, chaotic world where human weapons fail.

Part 2: The Wise King

Having gained great fame and treasure, Beowulf returns to Geatland. After his king’s death, he becomes a wise and just ruler, protecting his people and maintaining peace for fifty peaceful years through strength and diplomacy.

Battle 3: The Dragon

A dragon, symbolizing greed, death, and the destructive power of time, is awakened when a slave steals a cup from its hoard. The now-aged Beowulf faces it alone as a final act of selfless sacrifice to protect his people, knowing he will likely die.

Conclusion: Heroic Legacy

Aided only by the loyal Wiglaf, Beowulf slays the dragon but is mortally wounded by its venomous bite. His death marks the end of an era of heroes. He is mourned as the greatest of kings, and his funeral pyre solidifies his eternal fame (lof), completing the poem’s elegiac circle.